Jarrad Seng: Picking up on the Vibe

W I T H J A R R A D S E N G

You’d be hard pressed to look at photography in Perth without coming across Jarrad Seng’s work. He’s a highly energetic and prodigiously talented photographer with his hands in pretty much every photography project in Perth – from coverage of music festivals and photography of the Perth International Arts Festival to his work as a photographic mentor at the Awesome Arts Festival.

Jarrad Seng’s trajectory in photography is the stuff of child geniuses. He’s gone from picking up his first digital SLR camera a few years ago, to covering major events in this fair burg with work picked up by print and online media. Jarrad’s enthusiasm for the medium is highly infectious – he is someone for whom photography becomes a means to explore new experiences. In how own words: “I love doing everything; any opportunity that comes up is a bit of an adventure. It’s probably one of my biggest flaws, that I take up too many things.””

This “flaw” has certainly seen him involved in a diverse range of projects including (at time of writing) his joining UK singer-songwriter Passenger on tour as the band’s resident photographer, his mentoring Indigenous young people in the Pilbara with Awesome Arts, a massive commission for the Perth International Arts Festival (still under wraps at time of writing), coordinating “Beyond the Barrier” a group exhibition of music photography, his work with young people who have experienced homelessness in the “Home Is Where My Heart Is” photography project and exhibition and mentoring young photographers at ArtsCamp and the Hyperfest Music Festival. In amongst all this, he manages to find time to throw his own solo exhibition – “Portraits of Tanzania”.

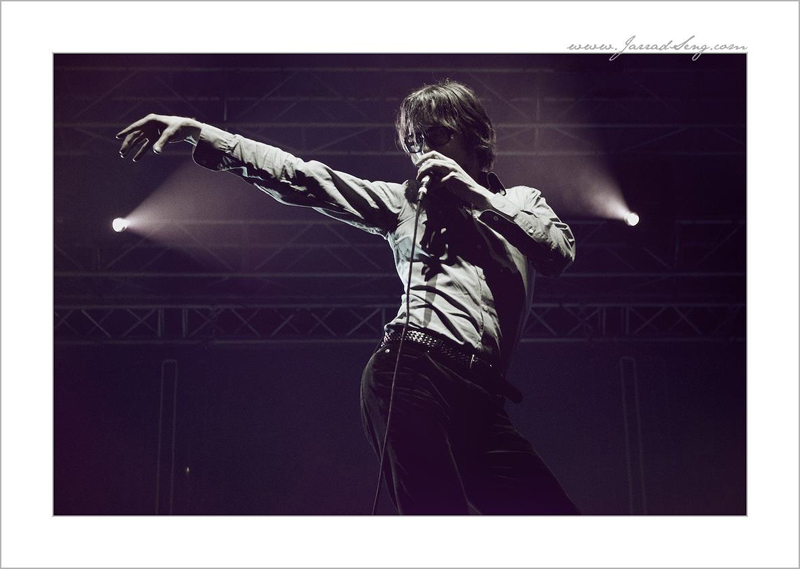

In this Masterclass, Jarrad talks about his first love: music photography, and the way he prepares for and shoots performers and events at music festivals.

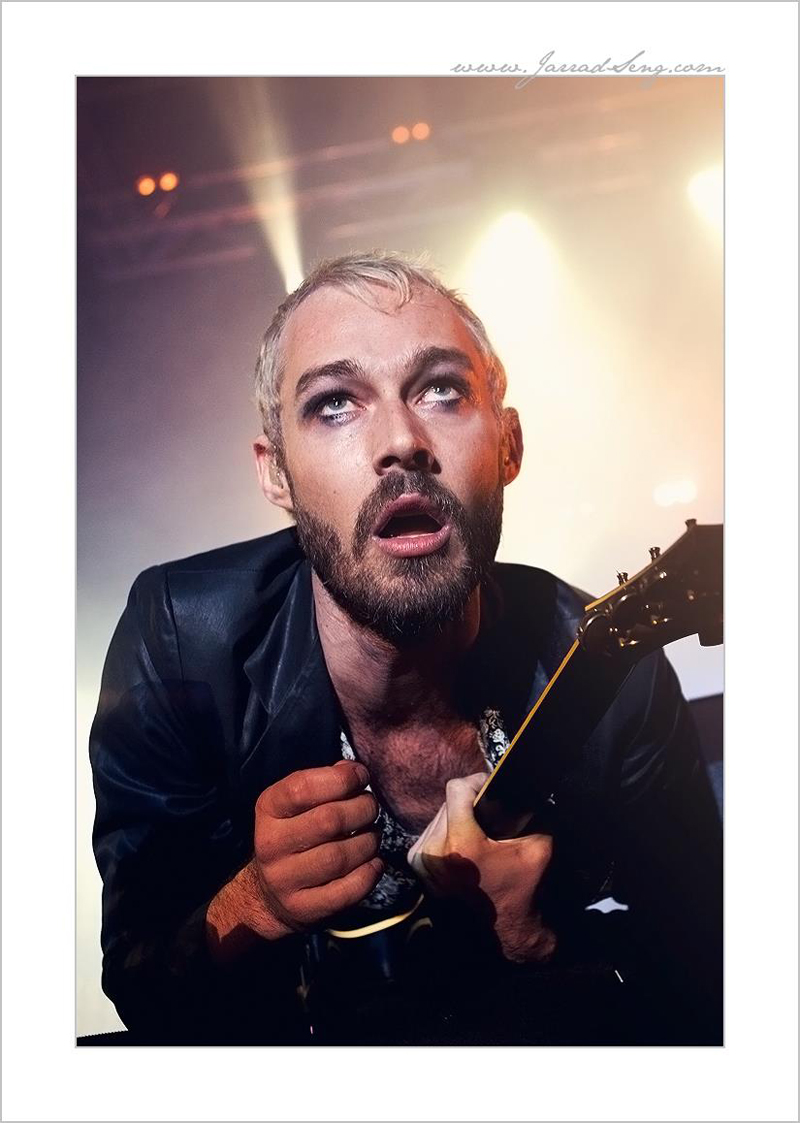

Camera: Canon 40D, Lens: Canon 24-70mm f2.8 at 32mm, Exposure: f3.5, 1/160, ISO 800

Tell us a bit about how you took this photograph of singer, Daniel Johns.

This image of frontman Daniel Johns of Silverchair was taken at Groovin the Moo Festival in Bunbury in May 2010. I was shooting for WA Today at the time, and was really feeling the vibe of the festival.

The acts were all amazing, and I was getting some of the best festival shots I had ever taken in my (short) music photography career. In fact, a photo I took from Grinspoon’s earlier set ended up winning a Corona photography competition later that year.

But I consider this one of Daniel Johns my favourite music shot. I feel that the image has captured a fleeting moment of vulnerability (whether deliberate or not), and a raw glimpse or insight into this complex character. It’s not a typical music shot, that’s for sure. Of those I’ve taken thousands. But every now and then the artist gives you something special, and you have to be in the right place at the right time to capture it.

It’s an amazing picture, and an amazing portrait, and I’m particularly impressed that you managed to sense when this moment was going to occur. How do you watch out for these “special moments”?

I find it’s a combination of anticipation, positioning and luck. It’s pretty rare to get this close to a performer at a big music festival.

Photographers are confined to the photo pit, which is the area between the stage and the crowd barrier, and the stage is often above head height, making things very difficult with angles and distance. Luckily, at this stage of my career I didn’t own the ‘festival standard’ 70-200mm lens most festival photographers sport – if I had, there was no way I would have been able to get this kind of shot!

I remember this moment. Daniel Johns was (typically) going mental the entire time, but in the moments leading up to this image, I felt that something was going to happen and maneuvered myself into position right in front of him (standing at this stage).

Suddenly Johns gets down on his knees and leans forward over the stage. I was in prime position and couldn’t believe the photo opportunity I was getting. I shot this at 32mm so you can imagine how close his face would have been! Special moments like this are what gets the adrenaline pumping in the photo pit!

Are there any particular photographic challenges when you shoot bands? For example, how do you deal with low light, or the fact that you often have mixed lighting in the background, or mixed coloured lights?

There are a lot of challenges when shooting music, but that’s what makes it exciting. The most obvious is the low light – whilst generally, festival stages and major concerts are well lit and have great lighting, for the most part, other smaller venues aren’t going to have a fantastic amount of light to work with.

Then there’s the fact that the lighting is dynamic, changing in the blink of an eye, you have absolutely no control over what happens on stage, movement is constricted by the audience or the photo pit, and to top it all off you’re usually fighting for space with a handful of other photographers (or up to 30 at a major festival) also vying for the best spots.

And then there is the ‘three songs, no flash’ (every music photographer has heard this a million times) convention, which means that photographers are only allowed to shoot the first three songs (roughly 10 minutes), and then have to get out of the pit or crowd. That might sound pretty tight, but with more experience, you learn how to make the most of that time. You can actually take a lot of pictures in 10 minutes, it’s just a matter of keeping your head and getting the shots you want to get.

There is a lot of anticipation required. I would say one of the main skills you need as a music photographer is the ability to anticipate when the action is going to happen. It comes from experience and knowing music and going to a lot of concerts.

Anyway, those are some the challenges. But the reward can be a stunning image, with raw energy oozing through the lens.

How do these challenges translate into the way you shoot. For example, how do you deal with exposure when shooting music given the tight time frame and the challenges of low light or changing light?

Generally, I start out in aperture priority, probably wide open, and let the camera work out the situation with shutter speeds and whether it’s workable. I usually start at ISO 800 as a default. I’m happy if I can shoot at 800 but rarely go past ISO 1600. Once I’ve shot a few frames in aperture priority, I usually switch to manual for the rest of the set.

A lot of it has to do with anticipating and adapting to the changes in light, as well as the action unfolding on stage. Sometimes you’ll have blinding strobes flashing rapidly, other times the lights may stay static for the whole set. Music photography is about adapting to what’s in front of you, and making the most out of what you’re given.

Sounds like it takes a lot of experience to build that kind of anticipation and reaction! Do you have a general approach when shooting bands – for example, in terms of location, angles; how does this influence, for example, the focal lengths (and thus the lenses) you use?

I shoot with two cameras, but for a long while it was just one, the Canon 40D. Now, I shoot with a Canon 7D and a 5D Mark II and use a long lens on one body, and a wide anglelens on the other. I like using primes when I shoot.

When shooting bands, you’re quite limited in terms of the space you have – there’s the crowd, the barrier and the other photographers in the pit, so your mobility can be quite restricted. That’s when it will come in handy to have two camera bodies with varying lenses.

Above all, enjoy the music and soak in the atmosphere. Music concerts are my favourite place to be, and I try not to forget that whilst ‘working’.

Do you think there’s a “minimum set” of essential gear for a photographer wishing to get into music photography (eg. high ISO performance camera, fast lens)?

I’m wary of suggesting a “minimum set” of gear, as people shoot in so many different, creative ways. But very generally, if you want to be getting the kind of stunning live shots you see in magazines and posters – you’ll need a DSLR that can handle high ISO (I’ll often be shooting in the range of ISO 800 – 1600) as well as a lens set that is capable of reaching a wide aperture.

If you want the flexibility of being able to cover a diverse range of venues with varying lighting conditions, you’ll want a lens that can ideally reach an aperture of 2.8, or close to that. That said, I’ve seen amazing photos at narrower apertures – I’m just making the point that music photographers face a hugely diverse range of lighting conditions at concerts, and frankly most of the time it is not great and you’ll need to rely on that wide aperture to get usable shots.

My initial camera set up (which I maintained for about a year or so of shooting gigs) was simply a Canon 40D with a 50mm 1.8 and a 24-70mm 2.8. This is probably all you would need to cover the vast majority of gigs – something wide that can capture all the action on stage, as well as something which can shine in the low light. The 70-200mm beast also comes in handy for the larger productions.

Recently I’ve been using solely primes at concerts. It forces you to move your feet and get creative with your shots. After a while, shooting concerts can start to feel like a little repetitive, so changing it up is always refreshing.

And don’t forget ear plugs! I made that mistake at the start of my career, and I’m paying for it now.

I want to get back to the topic of anticipation – you’ve mentioned this a few times and I get the feeling that it’s a very important part of music photography: the difference between an average image and a fantastic image. Can you explain a bit more about this?

You are really looking for the right moment. That’s the exciting part for me. You have to know when something is coming: the jump in the air, the raised fist, the spray of beer. You pick up on the vibe of the music. When you have been doing it for a while, you’re able to anticipate the emotion because you are tapping into the energy of the band and the music.

It’s a bit like a game, especially when you have a high energy band. It’s like you’re a hunter, waiting for that moment – and you just have to be at the right place, have the right setting, ready to shoot.

You use the wide-angle and fish-eye lenses often in your photography. Is there a reason for this? What do you think the fish-eye or ultra wide angle adds to the photograph?

I do love using the fish-eye lens, though it’s a lens that you need to use very carefully, deliberately and sparingly as to not descend into novelty. It can add another perspective, something fresh to change it up, or it can give you a view of the whole stage or the whole crowd. Though I think generally the lens is quite often overused for images that don’t suit it, which is something to be careful about.

An ultra distorted close-up may work nicely with a heavy metal or punk band, for example, but not for an acoustic folk set up. So, you need to think very carefully about the effect you are going for.

I’m going to backtrack a bit here and ask you to describe the photography that you do. Your body of work seems very broad – weddings, events, travel, music, performances, portraiture. How did you get started, and how did you end up becoming such a flexible photographer?

Well, the reason I decided to pursue photography in the first place was to explore the world of music photography. So that’s where I started (rather dubiously I might add). I just wanted to be able to capture the intense energy and passion that I was seeing on stage week after week as a music journalist / music lover. I didn’t have any ambitions further than that, and would have been happy if that’s as far as it ever went.

Why music photography? You certainly shoot other subjects/genres but you say that consider music photography your specialty. What draws you to the subject?

Music is my passion. I was into music before everything else, before photography. And if I had to ever choose one to make a career out of, it would probably be music (if I had the talent!)

I’ve played in local bands and had some of the best experiences of my life there. And I actually started in music journalism, interviewing artists for magazines and reviewing concerts, but after a while I was drawn to the photography/visual side of things.

I’m in the zone when I’m in front of a band, camera in my hands. I feel at home, and there’s excitement in the challenge of capturing the unpredictability of what’s going to unfold on stage. I love the feeling of the bass vibrating through your body as you work. That eye contact with a fellow photographer when you know you’ve both just got that killer shot. I love yelling out and singing along to the music and nobody notices, it just becomes part of the atmosphere.

What makes a good photo for you? An exciting photo?

A good photo has to be amazing for me to want to show it to people. The photo needs to be something different, something unique, not ordinary, not something that is easy to get, not something that you’ve seen before. I guess that’s easier to achieve in the kind of stuff I do (as opposed to a landscape photographer or a portrait photographer), because there is always an element of unpredictability when you photograph music or events.

You recently exhibited a series of portraits you took while in Tanzania, called “Portraits of Tanzania”. Can you tell us a bit more about this project and how it came to be?

I’ve always loved both traveling, volunteering and exploring developing countries, so I combined this with a photography project in Tanzania at the start of the year. I volunteered at a school and an orphanage, and on the weekends traveled out to various villages and tribes to visit the Maasai people and take some portraits. It was my first solo exhibition, and let me tell you it was a very challenging and insightful journey! But it was immensely rewarding having my work on display, and seeing all the support I had from friends and family. All proceeds raised from the exhibition went towards fundraising for the various humanitarian organisations I worked with in Arusha.

You’re also getting really into video at the moment – like the “Smile | Tanzania” film and your filming of the live acoustic videos of Passenger.

It’s a tough call, but I’m starting to prefer the product of the video medium more so than photography. There’s something special about being able to add music to moving images, to create a certain atmosphere or story. Film is something I would love to make a career out of, but I think it’s something you really have to invest everything into which I can’t do in the foreseeable future!

For photographers who are keen to get into music photography – what advice do you have for them to get started? Obviously there’s the technical and soft skills sets, but in terms of being able to get noticed and to get offered jobs – any suggestions?

First and foremost you have to love music. It’s not about doing it to go to concerts for free. You won’t last long if all you want to get out of it is is free entry into gigs.

Start off as a volunteer. I started by shooting for places like Faster Louder or The Dwarf, volunteering as a photographer. The reality is, for a lot of things in the arts and creative industries, is that you will have to work for free initially; no one’s going to pay you if you have nothing to show. It’s tough, but if you love what you’re doing then you’ll push through easily.

It’s quite tough getting paid jobs in music photography because there are so many photographers searching for limited paid opportunities. It’s about building a portfolio, building a name for yourself and not pissing anyone off! Basically, my best advice would be to work hard, and be good to people. If you are a reliable worker, and you have great images to show, the work will come. If your images aren’t quite there yet, then keeping working hard and improving until they are.

It’s a pretty small community of veteran music photographers in Perth – it’s nice to see them at every festival and have a little catch up. It’s hard industry to crack, but money shouldn’t be your main motivator.

What do you see as being the essential skill set for a photographer looking to get into music photography?

Respect for other photographers, for the crowd and for the band. Be considerate of everyone else, the punters have paid to see this show and they don’t want an overzealous photographer blocking their view the entire set.

Being able to handle the pressure of the difficult conditions and timing restraints.

Develop a great sense of timing and the ability to adapt to changing situations.

And most of all – you must have a love for music.

Can you tell us your favourite music photographers in the Perth scene?

I have a great deal of respect for the Perth music photographer community. They are producing some stunning work which often doesn’t get recognised, which was part of the motivation behind the Beyond the Barrier Exhibition.

Names like Stuart Millen, Courtney McAllister, Miko Katze, Anthony Tran, Cam Iniss, Lisa Businovski and Ben Eenhoorn are stalwarts in the local music photography scene, and all consistently produce amazing work.

MASTERCLASS ACTIVITY

A good photo has to be amazing for me to want to show it to people. I’d want the photo to do something different, something unique, not ordinary, not something that is easy to get, not something that you’ve seen before..

One of the challenges in photography is to be singular and unique in your vision and creation. The act of producing an image that is completely original and unique is something that Jarrad deems important for photographers.

How unique do you consider the images you create? Have a look at recent images you have taken – do any of them stand out of the rest as being different?

YOUR TURN

In this Masterclass, Jarrad talks about picking up on the vibe – developing an intuitive understanding of the situation, be it an awareness of music, or the flow of action in an event.

This Masterclass activity is designed to help you develop your intuition as a photographer. You’ll need your camera and a prime lens – either a 24mm, 35mm or 50mm. If you do not have a prime lens, set the focal length on your zoom lens to one of these and stick to it.

- Find a situation in which you can immerse yourself. You might visit a particular location (eg. the city, the coast) or go to a public event where photography is permitted.

- Spend the first 30 to 45 minutes observing the flow of action in the setting. Do not take any pictures. Instead, watch and see if you can pick up on its vibe. Are there any elements in the situation that you can anticipate or predict? Are there elements which are completely random?

- When you’re ready, take photos of the climaxes or high points in the flow of action. Are you able to anticipate when the action or energies are going to peak?