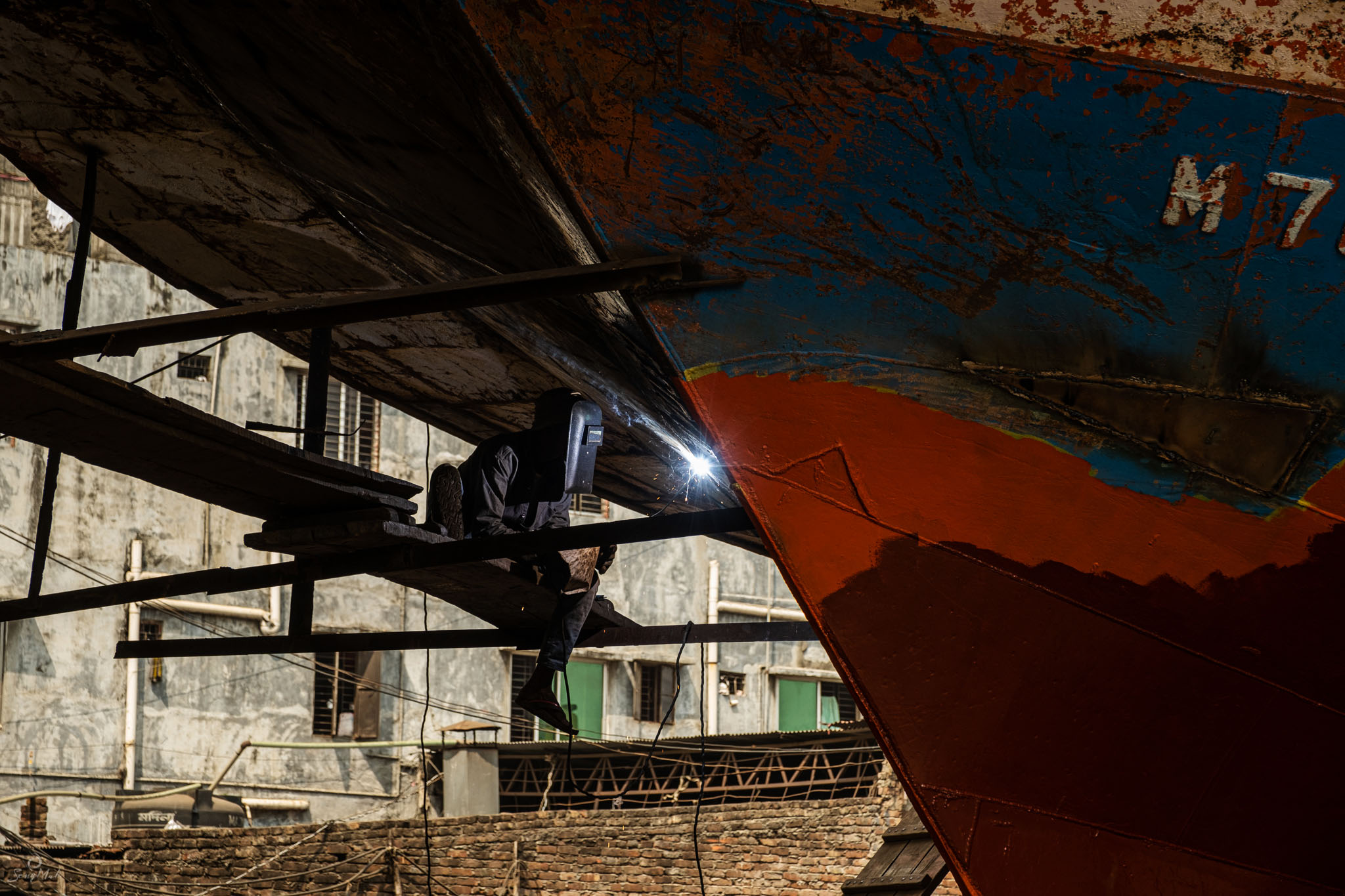

Very Hard Yakka – Shipbuilding in Dhaka

On a recent trip to Bangladesh, I visited and photographed the shipyard at Keraniganj on the banks of the Buriganga River in Dhaka. Dhaka is the capital of Bangladesh, a country that’s gaining worldwide recognition for its shipbuilding industry. While this might conjure up visions of high-tech assembly lines where sleek ocean vessels are mass produced, the reality in Dhaka is anything but. Ship building is all done by hand, by large teams of men and boys, in workplace conditions rife with physical hazards and toxic fumes.

Before a ship is built, an old ship must be broken down into its component parts and this is the function of the main shipyards. Strong, wiry men toil to pull apart the ponderous pieces of old ships, banging unwieldy dents and curves back into shape with hammers, and then rebuilding new vessels using a combination of new and recycled parts. In other sections of the shipyard, propellers are cast in underground furnaces (watch where you step as you may end up falling into one!) where oils and caustic fumes burn tracheas and lungs and make eyes water. Boys as young as seven or eight work here at the forges, their hands caked with so much oil, metal dust and silver paint that they turn metallic hued.

Amid all this cacophony of banging, welding, lifting, sweating and labouring, a community thrives; many workers live on site in small shacks and cabins adjoining shops that sell freshly cooked food and sundry items. Children run through the dusty laneways between buildings on work errands and there is a sense of community pride; that this is a working neighbourhood and a sense of professional dignity prevails. Everyone here works — from the youngest to the oldest. A boy who started begging for money from visitors is cuffed by an adult and spoken to in harsh tones. Goats (the source of meat in this mainly Muslim community) wander the lanes, sleeping in the shade cast by taller buildings. The heat from the sun and furnaces is unabating.

The shipyard is a dangerous workplace — men work without safety harnesses at heights that mean crippling injury or death if they fall; the fumes from the steel casting furnaces make breathing difficult and painful; they are caustic to the lungs. After an hour near the furnaces, I had to withdraw as I began to grow dizzy and nauseous from the fumes. And I had a rudimentary face mask; the locals work with little personal protective equipment much less respirators.

The shipyard at Keraniganj presents human labour in one of its rawest forms. Sequestered in our overly protective cocoons in developed countries like Australia, it is difficult for us to fathom the kind of lives these workers lead. The things we take for granted – such as safety, education and workplace protections – do not exist here. And yet here in the grubby, noisy and claustrophobic shipyard are instances of kindness and friendliness that seem so at odds with the environment. A young man, noting that I was feeling a little unwell, invited me into the shed of his shop, offered me his seat and turned an electric fan towards me, so that I might have a brief rest during my exploration. Shopkeepers welcomed me with a smile and patiently offered themselves for environmental portraits. The shipyard workers were always friendly and open to being approached and photographed, even if they were probably wondering why foreign visitors would find their hard labour so interesting.

It’s instances of such humanity that truly make this an emotive and rewarding travel experience. Beyond the photography that documents the harsh conditions in which these people work, it is exposure to this very human face in a community whose lives are so different from ours, that draws the connecting line of shared humanity between us all.

No Comments