Stumbling Stones and the Poetry of Interruption in Photography

Photography is often taught as the craft of guiding the viewer’s eye into the frame. Compositional techniques—leading lines, framing, rhythmic repetition—are treated as visual stepping stones that guide the gaze smoothly through an image. Yet photography is equally capable of cultivating interruptions: small visual moments that disrupt clarity, break flow, and make the viewer hesitate.

These interruptions can be regarded visual stumbling stones, elements within an image that halt or redirect perception. Camera club judges may dismiss them as “distractions” but that is far too reductive an assessment. Far from being indicative of poor technique, stumbling stones can be potent compositional devices that create tension, depth, and dynamism, inviting deeper engagement with the image.

Visual stumbling stones work in four inter-connected ways: they introduce micro-pauses in visual navigation of the frame; they can introduce productive distraction; they disrupt spatial expectation that energises the composition; and they create psychological friction that deepens the act of looking.

Each mode reveals a different dimension of what it means to see—and why stumbling can matter as much as stepping.

Micro-Pauses and the Rhythm of Visual Attention

A stumbling stone is a moment where the eye stops in its navigation of the scene within the frame of the photograph. It may be an oddly placed object, an ambiguous form, or a colour that clashes with the surrounding palette, or the intrusion of something unexpected. By compelling the viewer’s gaze to slow down, reconsider, and then continue, the stumbling stones encourage a more considered, deeper engagement with the image.

Photographers are often advised to avoid “busy images” because “the eye doesn’t know where to go.” But all this does is invite lazy readings of the image and the production of over-simplified compositions that don’t challenge viewers. (My hot take: we need to stop lauding the “rule of thirds” because it just encourages uncritical composition).

The work of William Eggleston is rich with micro-pauses. His images often contain elements that sit uncomfortably within the frame: a disembodied shadow, a garish patch of red, a fragment of a figure. These details don’t guide the viewer deeper into the image; they momentarily stall the gaze. But in doing so, they force the viewer to inhabit the picture more fully, to explore its corners, and to negotiate its spatial and emotional logic. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jul/08/made-in-memphis-william-eggleston)

William Eggleston

These pauses, whether gentle or jarring, teach us that visual meaning lies not only in movement, but in interruption.

Productive Distractions: Depth, Detail and Disorder

Stumbling stones are often dismissed as “distractions.” But distraction itself can generate visual engagament. The key distinction lies in whether a disruptive element adds to the image’s expressive capacity or undermines it.

Productive distractions enrich an image by providing narrative clues, emotional counterpoints, or unexpected tonal shifts. They complicate the picture in meaningful ways.

Destructive distractions are merely accidental: they confuse the composition without offering insight or intention.

It’s important to be able to distinguish between the two.

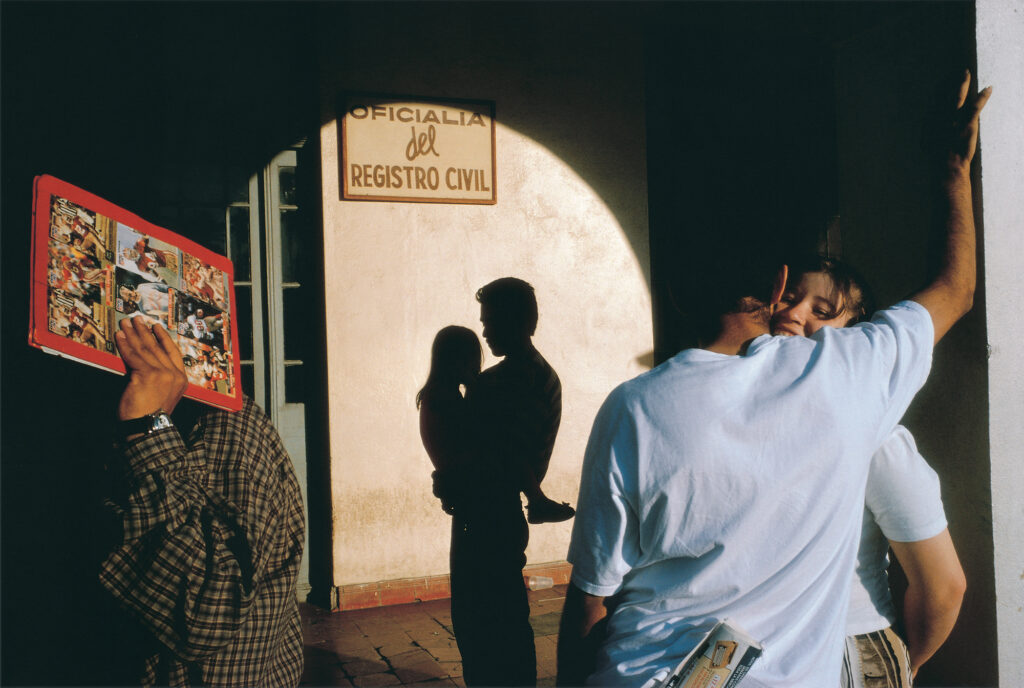

Street photography is a particularly fertile ground for productive distraction. Garry Winogrand famously embraced visual chaos: someone walking out of frame, a hand entering from nowhere, a poster partly torn, the background overflowing with activity, a half-visible sign. These are not compositional mistakes; they energise the frame and add an important patina to the representation of urban life, its chaos and beautiful unexpectedness. Winogrand’s stumbling stones also create powerful juxtapositions: a teenager’s sullen gaze vies for attention with the more romantic moment of a young couple caught in mid-kiss. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/oct/15/-sp-garry-winogrand-genius-american-street-photography)

Garry Winogrand

Nan Goldin

Similarly, Nan Goldin’s work embraces domestic disorder: cluttered rooms, bright flash reflections, stray objects sprawled across a bed or table. These elements do not detract from the intimacy of her images; they describe the intimacy (in all its chaotic fervour) of the spaces inhabited by the individuals she photographs. They convey that life is raw, lived, and disordered, and contribute to the emotional weight of her photographs.

Productive distraction is not about noise for its own sake; it is about using visual noise to tell a deeper truth or to bring the viewer deeper into the spaces of the story.

Spatial Disruption: Breaking Lines, Challenging Order

Traditional rules of composition seek to impose coherence to image making. But stumbling stones introduce spatial ambiguity: a sense that the picture cannot be read in one direction or from one vantage point. They may obstruct leading lines, produce conflicting vectors, or establish multiple competing focal points. The result is a frame that feels layered, contested, or unstable.

If spatial disruption is something you’d like to explore, then look no further than the work of Alex Webb. His densely layered colour photographs are filled with figures and objects that interrupt each other’s boundaries, so much so that his oeuvre is often humorously referred to as “migraine photographs”. Webb’s stumbling stones create not confusion but polyphony: many voices speaking at once, each interrupting and enriching the others. His images require viewers to navigate them, often stumbling through pockets of complexity before finding equilibrium. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/may/14/alex-webb-magnum-photographer-geoff-dyer)

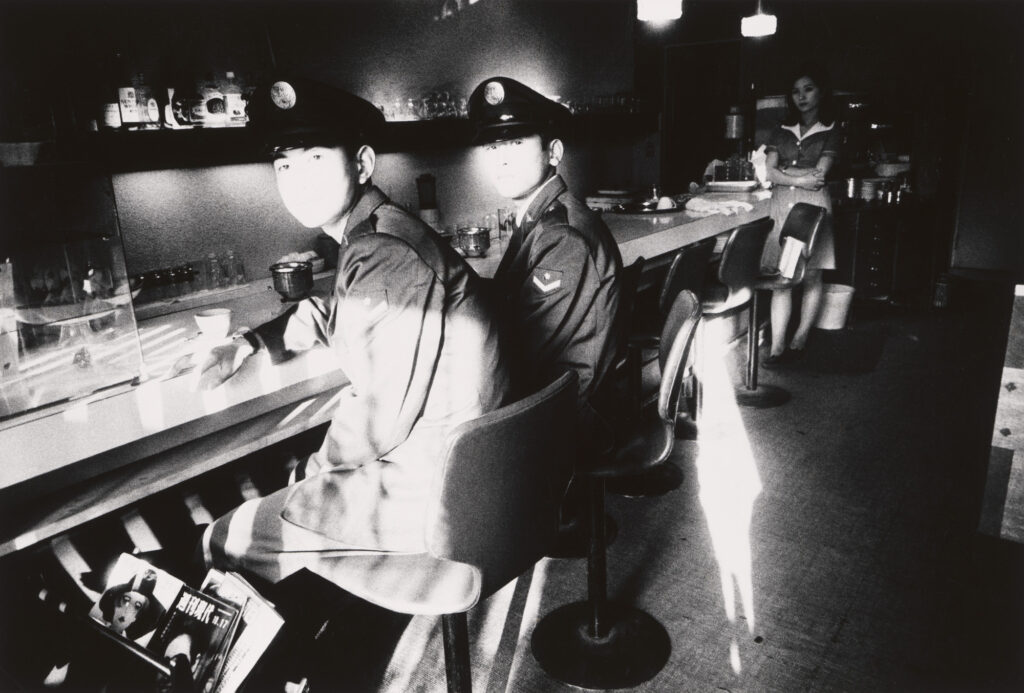

Daido Moriyama uses high contrast, blurred forms, and intrusive signage to fracture our reading of the space within an image or, at times, the image itself! His images feel like shards of sensations that are found on a gritty pavement. The stumbling stones in Moriyama’s work destabilise orientation, evoking the disoriented, sensory-overloaded experience of the street. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/oct/09/interview-daido-moriyama-photographers-gallery-london-retrospective)

Daido Moriyama

Creating Friction, Developing Tension, Prompting Curiosity

Stumbling stones ultimately operate on a psychological level. They upset expectations and introduce friction—a sense that the image cannot be absorbed instantly. This friction fosters curiosity, tension, and active inquiry. It reminds the viewer that looking is an active, interpretive act that isn’t always about instant gratification.

Trent Parke’s gritty black-and-white photographs capitalise on this effect. Harsh shafts of light obscure faces; sudden flares blow out part of the frame; shadows swallow details, figures overlap and hard, harsh highlights shape the scene. These stumbling stones generate emotional turbulence — mystery, anxiety, confusion — compelling the viewer to search the image for meaning. Parke’s Minutes to Midnight series is powerful because of the disarray and visual interruptions that break the scene. (https://www.streetshootr.com/video-trent-parke-on-making-minutes-to-midnight/)

Trent Parke

The Value of Stumbling Stones

Visual stumbling stones enrich photography by disrupting its flow, forcing the viewer to pause, question, and re-engage. They can:

- complicate the reading of an image,

- slow down the act of looking,

- expand interpretive possibilities,

- introduce tension and heighten emotion, and

- preserve the unpredictability of lived visual experience.

Where stepping stones lead us confidently into a photograph, stumbling stones remind us that seeing is non-linear, messy, and rich with unexpected turns.

These disruptions bring images to life by refusing to be too smooth, too directed, or too resolved, reminding us that vision is not smooth but uncertain, layered, and full of detours.

In a world saturated with streamlined, instant-gratification images, stumbling stones make photographs feel more alive, more human, and ultimately more rewarding to create and to behold.

Try incorporating stumbling stones into your photography

Here are some practical exercises you can use on your next photo walk, to train your eye to find, anticipate and incorporate visual stumbling stones meaningfully into your compositions.

The Peripheral Hunt: Compose Using What’s Not in Front of You

Goal: Learn to see the edges and peripheries as active compositional zones, where stumbling stones often are.

Exercise:

- Frame a scene and deliberately ignore the centre.

- Spend 30–60 seconds studying only the edges of your frame.

- Identify 2–3 elements that interrupt the frame (signs, limbs, reflections, objects entering or exiting).

- Make several images where these peripheral elements are essential to the composition.

- Repeat in different environments: a park, a street, a café, a room at home.

What you will learn: Sensitivity to subtle distractions and their potential to add to your composition.

Disruption Walk: Shoot Only What Interrupts Your Flow

Goal: Train your intuition to recognise productive distractions as opportunities.

Exercise:

- Go for a walk with the sole instruction: photograph only what “breaks” your gaze’s expected path in the frame.

- Examples include:

- a shadow cutting across a sidewalk

- a person entering the edge of the frame

- a sudden bright object

- a shape that disrupts a repetitive pattern

- Each time you feel your eye pause or hesitate, stop and photograph the source.

What you will learn: The ability to notice when your attention catches or is disrupted; not just what you think “should” be the subject (or what photography judges tell you).

The One-Minute Moment: Slow Looking Before Shooting

Goal: Build awareness of spatial disruptions before you press the shutter button.

Exercise:

At a chosen scene, you must:

- Stand still and observe for one full minute without shooting.

- Each time your eye pauses unexpectedly, mentally mark the spot.

- After the minute, photograph the scene with those stumbling zones intentionally

What you will learn: Recognition of interruptions and how they shape visual rhythm or movement in the frame.

Obstruction as Composition: Use What “Ruins” the Shot

Goal: Embrace objects that traditionally disrupt composition by make them central.

Exercise:

Photograph scenes where something is in the way:

- a pole crossing a face (or even sticking out of someone’s head)

- an intruding arm, branch or similar

- a car blocking part of a subject

- window glare or reflections

- a messy foreground element

Force yourself to make compositions around these obstructions rather than waiting for a clean shot.

What you will lean: Using what many consider “mistakes” as creative constraints that can generate tension and complexity in your composition.

Load the Frame with Competing Elements

Goal: Understand how multiple visual voices can coexist in an image. This is very much an exercise in layering and in being able to cognitively recognise pockets of moments within a chaotic frame.

Exercise:

- Choose a busy environment (market, festival, street, event etc).

- Create frames with at least three competing elements that vie for attention.

- Place them in different layers (foreground, mid-ground, background).

- Ensure none of them fully dominates the image.

Try building compositions in which stumbling stones and the “main” subject have equal weight.

What you will learn: You will become comfortable with creating images that have visual density and will cultivate your ability to “organise complexity” in your framing.

Richard Plumb

13/12/2025 at 10:24 aminspirational article. Have come across some studio portraiture where layers of backdrops/fabrics &/or studio equipment are deliberately left in frame. At first I found them not to my clean scene trained eye, but yes they make you pause in the image.

sengmah

05/01/2026 at 2:55 pmThanks Richard. I have seen these and I think it’s all part of a style that is linked to the authenticity of the image? So that viewers are aware that it is a studio piece?